Uterine Rupture in a Tertiary Hospital North Central Nigeria: Unending Maternal Tragedy

*Corresponding Author(s):

Ochima OnaziDepartment Of Obstetrics And Gynaecology, Federal Medical Centre, Keffi, Nigeria

Tel:+234 8036313556,

Email:otsima179@gmail.com

Abstract

Uterine rupture is an obstetric emergency with unacceptably high perinatal and maternal morbidity and mortality especially in areas with poorly developed maternal and child health care services. Timely recognition, adequate resuscitation and appropriate intervention are keys in reducing the negative impacts. The study was to determine the incidence, patient’s socio-demographic characteristics, possible risk factors and feto-maternal outcome of uterine rupture at Federal Medical centre Keffi North Central Nigeria. This was a 4-year retrospective review of all cases of uterine rupture seen and managed at Federal Medical Centre Keffi between 1st January 2016 and 31st December 2019. Relevant information were extracted and analysed from the hospital electronic medical records in both Labour ward and Maternity theatre. Results were presented in tables, percentages and charts. There were a total of 37 cases of uterine rupture out of 5288 deliveries giving a prevalence rate of 0.7% or 1 in 143 deliveries. Majority (81.1%) of the patients were aged 20-34 years and 73% were multiparous. 18 (48.6%) patients had scar uterus mostly previous caesarean section (94.4%) and well over half (59.5%) of the patients were un booked. Only 12 (32.4%) of the patients gave a history of use of utero-tonics. The commonest site of rupture was anterior (62.2%). All patients had laparatomy during which 20 (54.1%) had uterine repair only, 11 (29.7%) had uterine repair plus BTL and 6 (16.2%) had emergency abdominal hysterectomy for uncontrollable haemorrhage. Majority of the patients (89.2%) had primary postpartum haemorrhage necessitating blood transfusion in all but 4 of the patients. A case of maternal mortality was recorded. The perinatal mortality rate was 86.5%.

Conclusion: Uterine rupture remains a significant health risk to our women during child birth despite advances in medical science and health care services.

Keywords

Fetomaternal outcome; Risk factors; Scar uterus; Uterine rupture

INTRODUCTION

Uterine rupture is a life threatening complication of pregnancy and child birth with un-acceptably high perinatal and maternal morbidity and mortality [1]. Timely recognition, adequate resuscitation and appropriate interventions are cardinal to successful outcome. The impact can be far reaching especially in areas with absent or poorly developed maternal and child health care services. Uterine rupture and its squeal can be devastating not only to the woman and her family but to the clinician and the society. It is often a reflection of the poor quality of obstetric care in particular and the deplorable state of health care delivery in a society in general. Uterine rupture may involve separation of the entire thickness of the walls of the uterus (complete) or sparing the visceral peritoneum (partial rupture) [2]. With complete rupture, the foetus may be partly or wholly extruded into the peritoneal cavity making foetal salvage rate dismal [3]. Foetal compromise is usually due to hypoxia or/and maternal hypovolemia from excessive haemorrhage.

While the incidence and case fatality is low in developed countries the opposite is true for developing countries with rising incidence and case fatality partly due to prolonged obstructed labour, very deplorable health care services occasioned by long standing neglect by relevant authorities, dismal health care financing, poverty, women aversion to early and timely operative interventions, un-regulated activities of unskilled birth attendants and inappropriate use of uterotonics [4,5]. Globally the incidence of uterine rupture is low, 1 in 1416 (0.07%) pregnancies, the incidence among women with unscarred uteri in developed countries is even lower1 in 8434 (0.012%) however there is an 8 fold increase incidence of 0.11% (1 in 920) in developing countries [6]. In Nigeria reported rates of uterine rupture are 1 in 164 (0.61%), 1 in 172 (0.58%), 1 in 103 (0.97%), 1 in 210 (0.47%) and 1 in 117 (0.85%) deliveries in Lagos, Benin city, Enugu, Ilorin and Abuja respectively [7-11].

Common predisposing factors to uterine rupture includes: neglected obstructed labour, grandmultparity, scarred uterus, women aversion to early and timely operative deliveries which is seen as obstetric failure fuelled by ignorance and illiteracy, others are uterine instrumentation, blunt abdominal trauma and inappropriate use of uterotonics [12]. Some of the known foetal complications include need for admission to neonatal intensive care unit, foetal hypoxia and neonatal death while obstetric haemorrhage, hypovolemic shock, hysterectomy and death are maternal complications especially when cases presents late and medical care is suboptimal.

MATERIALS AND METHOD

This was a 4-year retrospective review of all cases of uterine rupture seen and managed at Federal Medical Centre Keffi between 1st January 2016 and 31st December 2019. The case records of patients seen and managed for uterine rupture were retrieved from the hospital electronic medical records in both Labour ward and Maternity theatre. Relevant information such as socio-demographic profile, booking status, previous uterine scar, use of oxytocics in index pregnancy, place of initial treatment, duration of labour, nature and site of uterine rupture, type of surgery and feto-maternal outcome were extracted and analysed using SPSS statistical software (SPSS, Chicago IL USA) version 25. Results were presented in tables, percentages and charts.

RESULTS

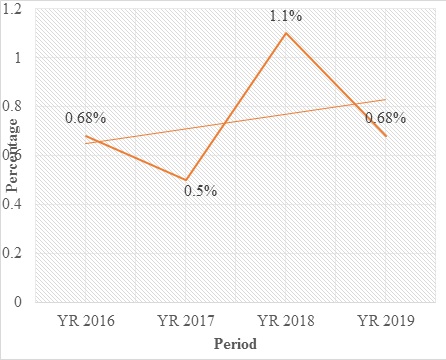

There were a total number of 37 cases of uterine rupture out of 5288 deliveries giving a prevalence rate of 0.7% or 1 in 143 deliveries. The annual trend ranged from 0.5% to 1.1% with the highest rate of 1.1% or 1 in 94 deliveries in 2018 after a drop in the previous year (0.5% or 1 in 199 deliveries).

Socio-demographic characteristics

The age range of the patients was 19 -38 years with a mean of 29.73 ± 4.23, majority (81.1%) were aged 20-34 years. 73% were multiparous while 13.5% were Grand multiparous. House wives constituted 54.1% (Table 1)

|

Variables |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

Age (years) |

||

|

20-24 yrs. |

4 |

10.8 |

|

25 – 29 yrs. |

12 |

32.4 |

|

30-34 yrs |

15 |

40.5 |

|

35-39 yrs. |

6 |

16.2 |

|

Mean ±SD; min.; max. |

29.73 ±4.23; 20; 38 |

|

|

Occupation |

||

|

Trading |

14 |

37.8 |

|

Housewife |

20 |

54.1 |

|

Farming |

1 |

2.7 |

|

Artisan |

2 |

5.4 |

|

Parity |

||

|

Primiparous |

5 |

13.5 |

|

Multiparous |

27 |

73.0 |

|

Grand-multiparous |

5 |

13.5 |

|

Mean ±SD; min.; max. |

3.25 ±1.42; 1; 7 |

|

|

Booking status |

||

|

Booked |

15 |

40.5 |

|

Unbooked |

22 |

59.5 |

Table 1: Socio-demographic profile of parturient.

Risk factors

Most of the patients (59.5%) were unbooked, 18 (48.6%) patients had scar uterus mostly previous caesarean section (94.4%) and about 54.1% were initially managed by an unskilled birth attendants. Only 12 (32.4%) of the patients gave a history of use of utero-tonics of which oxytocin use accounted for 75% (Table 2).

|

Variables |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

Place of initial management |

||

|

Skilled birth attendant |

14 |

37.8 |

|

Unskilled birth attendant |

20 |

54.1 |

|

Unspecified |

3 |

8.1% |

|

Duration of labour (>12hours) |

||

|

Yes |

18 |

48.6 |

|

No |

19 |

51.4 |

|

Use of uterotonics |

||

|

Yes |

12 |

32.4 |

|

No |

25 |

67.6 |

|

Type of uterotonics |

||

|

Misoprostol |

3 |

25.0 |

|

Oxytocin |

9 |

75.0 |

Table 2: Labour management.

Maternal outcome

Majority of the uterine rupture was a complete rupture (86.5%) commonly anterior (62.2%), other sites are posterior (21.6%) and lateral rupture (16.2%). All patients had laparatomy during which 20 (54.1%) had uterine repair only, 11 (29.7%) had uterine repair plus BTL and 6 (16.2%) had emergency abdominal hysterectomy for uncontrollable haemorrhage. Majority of the patients (89.2%) had primary postpartum haemorrhage losing more than 1000ml of blood with mean blood loss of 2415 ml. All but 4 of the patients had blood transfusion, 16.2% had febrile illness and 21.6% had wound sepsis. A case of maternal death was recorded due to late presentation and uncontrollable haemorrhage (Table 3).

|

Variables |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

Type of rupture |

|

|

|

Partial |

5 |

13.5 |

|

Complete |

32 |

86.5 |

|

Site of rupture |

||

|

Anterior |

23 |

62.2 |

|

Posterior |

8 |

21.6 |

|

Lateral |

6 |

16.2 |

|

Type of surgery |

||

|

Repair only |

20 |

54.1 |

|

Repair with BTL |

11 |

29.7 |

|

Hysterectomy |

6 |

16.2 |

|

Haemo-peritoneum |

||

|

</=500 mls. |

33 |

89.2 |

|

501 - 750 mls. |

1 |

2.7 |

|

751 - 1000 mls. |

3 |

8.1 |

|

Mean ±SD; min.; max. |

330.83 ±266.84; 100; 1000 |

|

|

Estimated blood loss |

||

|

751 - 1000 mls |

4 |

10.8 |

|

Above1000 mls |

33 |

89.2 |

|

Mean ±SD |

2415.2 ±1298.6; 1000; 8000 |

|

|

Variables |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

Blood transfused |

||

|

Yes |

33 |

89.2 |

|

No |

4 |

10.8 |

|

Mean unit of blood transfused ±SD; min.; max. 3.13 ±1.64; 1; 8 |

||

|

Febrile illness |

||

|

Yes |

6 |

16.2 |

|

No |

31 |

83.8 |

|

Wound sepsis |

||

|

Yes |

8 |

21.6 |

|

No |

29 |

78.4 |

|

Mother alive |

||

|

Yes |

36 |

97.3 |

|

No |

1 |

2.7 |

Table 3: Maternal outcome.

Fetal outcome

Only five (5) or 13.5% of the babies were salvaged of which four (4) had Apgar score >7 in the 1st and fifth minutes. The perinatal mortality rate was 86.5%. Majority of the babies (29 or 78.4%) were of average birth weights (2.5-<4 Kg), only 5 (five) or 13.5% were macrosomic (4 kg and above) (Table 4).

|

Variables |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

Fresh still birth |

||

|

Yes |

32 |

86.5 |

|

Alive |

5 |

13.5 |

|

Apgar score 1st minute |

||

|

<7 |

1 |

20.0 |

|

7+ |

4 |

80.0 |

|

Mean ±SD; min.; max. |

2.13 ±3.44; 0.0; 8.0 |

|

|

Apgar score 5th minute |

||

|

<7 |

1 |

20.0 |

|

7+ |

4 |

80.0 |

|

Mean ±SD; min.; max. |

8.20 ±1.79; 5.00; 9.00 |

|

|

Birth weight |

||

|

Low (<2.5 kg) |

3 |

8.1 |

|

Normal (2.5 - 3.9 kg) |

29 |

78.4 |

|

Macrosomic (4kg & above) |

5 |

13.5 |

|

Mean ±SD; min.; max. |

3.18±0.74; 1.20; 5.10 |

|

Table 4: Foetal Outcome.

DISCUSSION

There were 5288 deliveries with 37 cases of uterine rupture between 1st January 2016 and 31st December 2019 (0.7% or 1 in 143 deliveries) (Figure 1). This figure is higher than that of Lagos, Benin city and Ilorin [7,8,10]. Most of our women had no ante natal care as 59.5% were un-booked hence their pregnancies were not supervised, managed initially by unskilled birth attendants and presented late in labour. The yearly trend showed a sharp rise from 0.5% (1 in 199) in 2017 to 1.1% (1 in 94) in 2018 before dropping to 0.68% (1 in 147) in 2019. This period of rise may not be unconnected to the protracted junior staff industrial dispute in the hospital in the 2nd quarter of that year. Grand-multiparity has been associated with increased risk of uterine rupture [13] however in this study only 13.5% (5/37) cases was recorded among women with five and above deliveries. Majority (73%) have 2-4 deliveries.

Figure 1: yearly trend of uterine rupture.

Figure 1: yearly trend of uterine rupture.

Most of the patients with uterine rupture were aged between 20 and 34 years (83.8%), this group constituted the majority of our obstetric population. Contrary to some studies [4,5,12] uterine rupture was higher in women with unscarred uterus 51.4% (19/37), this may be that women with previous uterine scar may have been counselled on the danger of home delivery and are more likely to seek medical care in case of emergencies. The other possible explanation may be that caesarean section now is via lower segment uterine incision unlike previously when classical scar is common. Similar finding was recorded in Bamako- Mali where majority had no previous uterine scar [13]. It is also higher among those without oxytocics use (67.6%) the contribution of oxytocin has been equivocal [4,14,15]. A good number of the patients were initially managed by unskilled birth attendant 54.1%. This may have accounted for the late presentation in hospital. Poverty, ignorance aversion to operative deliveries and poor access to quality health care are some of the factors pushing these women to seek care elsewhere.

One case of maternal death was recorded (mortality of 2.7%), she had presented very late, dehydrated, anaemic and subsequently developed irreversible hypovolemic shock. The commonest maternal complication was haemorrhage with average blood loss of 2415ml necessitating blood transfusion in all but four of the women. Other complications are wound sepsis and febrile illness. All the cases were intrapartum rupture of which 86.5% was a complete rupture. Anterior rupture was the commonest site (62.2%) followed by posterior and then lateral rupture. Lateral rupture is usually associated with more bleeding as it may involve major blood vessels. Management largely depend on clinical presentation the extent of rupture, ability to secure adequate haemostasis, experience of the surgeon and the future obstetric desire of the patient. Most of our patients had laparatomy and simple uterine repair (54.1%) however 29.7% had in addition Bilateral Tubal Ligation (BTL) while 16.2% had abdominal hysterectomy for uncontrollable bleeding. The rate of hysterectomy was higher in some series probably due to strict selection criteria [13]. The perinatal mortality was very high (86.5%), this may be due to the fact that 86.5% was a complete rupture with the babies extruded into the peritoneal cavity making fetal salvage near impossible. This is consistent with other studies [3].

CONCLUSION

Uterine rupture remains a significant health risk to our women during child birth in this part of the world despite advances in medical science. Late presentation and poor utilization of standard health care services remains a major contributor to this monster.

RECOMMENDATION

Quality and affordable health care services should be made available and women should be encouraged to access care during pregnancy and delivery. Lower levels of health care facilities should know their limits and make referral of patients early. Timely recognition, adequate resuscitation and appropriate intervention are keys for successful outcome.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Fabamwo AO, Akinola OI, Tayo A, Akpan E (2008) Rupture Of The Gravid Uterus: A Never-Ending Obstetric Disaster! The Ikeja Experience. The Internet journal of gynecology and obstetrics 10.

- Cunningham FG, Leveno KJ, Bloom SL, Hauth JC, Rouse DJ, et al. (2010) Parturition. In: Cunningham FG, Leveno KJ, Bloom SL, Hauth JC, Rouse DJ, et al. (eds.). Williams Obstetrics (23rdedn). McGraw-Hill, New York, USA.

- Kaczmarczyk M, Sparén P, Terry P, Cnattingius S (2007) Risk Factors for Uterine Rupture and Neonatal Consequences of Uterine Rupture: A Population-Based Study of Successive Pregnancies in Sweden. BJOG 114: 1208-1214.

- Golan A, Sandbank O, Rubin A (1980) Rupture of the Pregnant Uterus. Obstet Gynecol 56: 549-554.

- Schrinsky DC, Benson RC (1978) Rupture of the Pregnant Uterus: A Review. Obstet Gynecol Surv 33: 217-232.

- Nahum GG, Quynh K (2018) Uterine Rupture in Pregnancy. Drugs & Diseases.

- Adegbola O, Odeseye AK (2017) Uterine rupture at Lagos University Teaching Hospital. J Clin Sci 14:13-17.

- Osemwenkha PA, Osaikhuwuomwan JA (2016) A 10-year review of uterine rupture and its outcome in the University of Benin Teaching Hospital, Benin City. Niger J Surg Sci 26: 1-4.

- Ezegwui HU, Nwogu-Ikojo EE (2005) Trends in Uterine Rupture in Enugu, Nigeria. J Obstet Gynaecol 25: 260-262.

- Aboyeji AP, Ijaiya MD, Yahaya UR (2001) Ruptured Uterus: A Study of 100 Consecutive Cases in Ilorin, Nigeria. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 27: 341-348.

- Akaba GO, Onafowokan O, Offiong RA, Omonua K, Ekele BA (2013) Uterine Rupture: Trends and Feto-Maternal Outcome in a Nigerian Teaching Hospital. Niger J Med 22: 304-308.

- Gardeil F, Daly S, Turner MJ (1994) Uterine Rupture in Pregnancy Reviewed. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 56: 107-110.

- Sima M, Traoré MS, Kanté I, Coulibaly A, Koné K, et at. (2020) Therapeutic, Clinical And Prognostic Aspects Of Uterine Rupture In The Point G Teaching Hospital, Bamako, Mali. J Repro Med Gynecol Obstet 5: 037.

- Mokgokong ET, Marivate M (1976) Treatment of the Ruptured Uterus. S Afr Med J 50: 1621-1624.

- Plauche WC, Von Almen W, Muller R (1984) Catastrophic Uterine Rupture. Obstet Gynecol 64: 792-797.

Citation: Ochima O, Tivkaa DT (2020) Uterine Rupture in a Tertiary Hospital North Central Nigeria: Unending Maternal Tragedy. J Reprod Med Gynecol Obstet 5: 049.

Copyright: © 2020 Ochima Onazi, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.